White Danger: Double-Mindedness, Violence, and the Confusion of Whiteness

“I guess I just don’t understand what boundaries are.”

I remember the exact location, the light, the positions of our bodies in space, when a white man said these words to me. He had a pattern of violating boundaries and agreements, and would frequently admit those violations while simultaneously claiming confusion that the boundaries and agreements even existed. When confronted with this pattern, he belligerently denied any capacity to understand his own behavior.

For me, it was a revelation. I will always be grateful for this lesson.

It has been many years, but I often think of this moment when I consider the danger posed by white people, and by white men specifically, to people of color, and to Black people especially. I am seasoned enough by living to know that the white people to fear are not only those who arm themselves, but also those who believe themselves to be disarmed. I have learned that this type of white person is, in certain regards, infinitely more dangerous because they believe themself to be incapable of causing harm, and in fact separate from harm doers.

"Some people are more dangerous because they believe themselves to be benign. Those of us who have survived sustained harm understand that patterns of harm are actually the opposite of benign: they are malignant." - Autumn Brown, AORTA

Some people are more dangerous because they believe themselves to be benign. Those of us who have survived sustained harm understand that patterns of harm are actually the opposite of benign: they are malignant. And indeed, whiteness, which I define as the ideology of domination that intentionally and unintentionally expresses itself through the bodies of white people, operates much like a cancer, eroding and consuming. This erosion can be slow and, at times, nearly imperceptible. The lies, the betrayals of trust, the cowardice and shame, the lack of moral compass and the denial of harm-doing, enacts its first and perhaps most lasting damage to the psyche of the white person. A white person who is being consumed by whiteness may appear, to himself and others, helpless to do anything about this. A society being consumed by whiteness, by white danger, may appear to be helpless to do anything about it. And indeed our first response to this decompensation is often to feel concern and compassion, or exasperation and laughter. We should not be laughing, but we are. Laughter escapes the body when the nervous system is overwhelmed.

The confusion, denial, helplessness, and base absurdity of a white person, confronted with the impact of their own harmful behavior, is dangerous. This is not to say that it is equivocally more or less dangerous than an explicit show of domination. But it is a clear and present danger. It has long term consequences and an insidious nature, that is wound together in certitude with the explicit show of domination.

I have known many white people who cause harm and act surprised about it. It took me years to understand this behavior. The phenomenon wherein a white person denies their own reality through a pretense of confusion, in turn induces confusion for any witness. We may feel gaslit, at risk of questioning our own sight. What I have noticed, over years of observation, is that when white people repeatedly cause harm to people of color, and deny it, they are very effective at asserting an alternate reality to the one that white people themselves are directly experiencing, and they are especially effective at asserting their own victimization within that alternate reality.

We, who witness these assertions of an alternate reality, in which the white person (or, lately, white society) is the victim, may think it is autonomic because the behavior comes with such a high level of facility, so as to appear involuntary. And in a way, it is. Because they believe it, we believe it. They seem helpless and so they must be.

That is, indeed, the entire point. In reality, this assertion of victimization is a highly sophisticated and elegant defense mechanism, a product of a highly sophisticated and elegant psychology, that supports participation in white supremacy, a system that is most highly effective at replicating itself.

***

“The shaping of white identity, premised on exclusion, is a central thread in the national narrative, bound up with capitalist development in general and manifested, in one way or another, to one degree or another, in every political, social and cultural institution.” -Linda Burnham, No Plans to Abandon Our Freedom Dreams

Increasingly I find myself turning towards the framework of double-mindedness, the twin conscious and unconscious behavior of people who engage in harmful or abusive behaviors, while simultaneously being unaware of causing harm to others, and even believing themselves to be incapable of causing harm. This type of consciousness is not specific to whiteness. In fact, it permeates most relationships where dominance and abuse is present. White identity is one such space, as it must be differentiated from other cultural and ethnic identities (including those which were subsumed into whiteness in order to manifest it), inasmuch as its foundational operating principle is the abuse of power. Application of the framework of double-mindedness* to the phenomenon of whiteness has unlocked a deeper level of understanding for me, and in my work with white people.

"double-mindedness: the twin conscious and unconscious behavior of people who engage in harmful or abusive behaviors, while simultaneously being unaware of causing harm to others, and even believing themselves to be incapable of causing harm." - Autumn Brown, AORTA

Double-mindedness in white people is, at once, a core function of, and a dangerous side effect of, living within the coevolving systems of capitalism and white supremacy - what Cedric Robinson rightly articulated as “racial capitalism,” understanding that racialization is endemic to capitalism, not distinct from it. The function of double-mindedness has roots as old as the system itself. How else would one remain functional inside a socio-economic system that confers benefits to white people through violence against, and at the extractive expense of, Black and indigenous people and people of color? A white person must become effective at dissociating. The heart, the brain, the bodymind itself, becomes adept at running offline, quieting the systems that would register ongoing harm, violence, and injustice as a disturbance.

Generations of white people in the United States have learned and practiced this type of dissociation. It comes with a high level of facility, just as the dissociations of Black and brown people in order to navigate the chronic threat of white supremacy on our bodies and psyches, comes with a high level of facility. The dissociation of double-mindedness in white people is supported by hundreds of years of policy, legislation, and political process that allow, even require, individual white people to relate to Black and indigenous people and people of color as a lesser class of human. The socialization of whiteness deems the non-white class unworthy of the same empathic response as fellow white people.

Ideology plays a key role as well. The entire system of racial capitalism is constructed on a narrative of white superiority, and most importantly, the inherent “goodness” of white people of European descent, an inheritance of the unique historical overlay of Christian hegemony and colonization, wherein the role of the European Christian missionary was to “subdue” Black and indigenous communities through conversion intent on saving their souls. Those who were not willing to be converted were tortured, raped, and murdered.

We cannot underestimate the impact of this legacy of violence on the psyche of white Americans. We cannot overestimate the conditioning toward violence within the cultural trauma of whiteness. Whiteness is not just a cultural trauma of erasure: the ways that European communities, at times by choice and at times by violent force, gave up their cultures of origin for the sake of assimilation into the system of white supremacy. Whiteness is also a cultural trauma of violence: enacting violence, witnessing violence, consenting to violence, and celebrating violence. Consider that we are only a generation or two out from a period in which lynchings were a Sunday affair and white children posed for photos beneath the tortured, mutilated, and deceased bodies of Black people who lived in their communities. (If we can be considered beyond this, which is arguable). Consider that even now, there are white people who reactively celebrate Black death at the hands of the police, as if protesting for the civil right to do so. Consider the split consciousness of the white person who at once subscribes to religious vows or values, who engages in spiritual practices, who meditates on the nature of compassion, and also experiences and re-experiences pleasure through violence.

Consider that we are all connected to this legacy and this conditioning.

White status is, and has always been, a contested space. Just as the space of “other” is contested. But as our most recent elections and attempted coup have laid bare, the core tenets of white status and the core beliefs of white supremacy have remained relatively stable for centuries. It is only the individual and collective dissociative state in white people, arising from witnessing and participating in daily systemic violence that benefits the white community, that would have anyone believing otherwise. That state, at its essence, is double-mindedness. On the one hand, a white person is engaged in a system of violence and harm, and is capable of causing enormous harm to those who are targeted by and vulnerable within that system. For evidence of this, simply look to any recent news story reporting on white women calling the police on Black people who are engaged in everyday behaviors of life. The same white women at the heart of these stories believe themselves to be benign, incapable of causing harm, because of an internalized narrative of white goodness and white neutrality.

Individual and interpersonal racialized violence and racial harm often occurs within the dissociated state, and is enacted by the dissociated body. A demand for accountability in the aftermath of this behavior, or even something as simple as “feedback” on harmful behavior, is received as an assault. A white person, believing themself to be benign, either fights or collapses in response to learning about the behavior taking place within the dissociative state. These days we casually and frustratedly refer to “white tears” and “white fragility” as we throw up our hands in exasperation, disbelieving that a white person could truly not see that their behavior was problematic or violent. But in actuality, white tears and white fragility are just one visible manifestation of the sophisticated defense mechanism of double-mindedness.

Consider this: If a white man experiences himself as a confused, helpless victim of his own lack of consciousness and understanding, he is not then responsible for his own behavior. No alternative behavior, no solution, no apology, and no internal work is then required. He may continue causing harm and enacting social, emotional, psychological, or physical violence in perpetuity, always and forever claiming that he does not understand, and could never understand, why his behavior is harmful. But his confusion and helplessness is not disconnected from an explicit show of domination. The former offers a path of distancing from the latter, assuaging guilt, soothing the ego, reassuring the white person of his goodness. He is protected, and his double-mindedness is intact.

There is a different path, albeit it is a harder one. Whereas the double-minded and unintegrated self is causing interpersonal and collective harm, the integrated self may actually be capable of interrupting patterns, of offering true apology and accountability, of taking responsibility for body, words, and decisions in real time. Hard, yes, but it is not, after all, so tall an order. Black and brown people, indigenous people, and people of color learn from a very young age that part of our job is to control ourselves, lest we die. White people instead learn that they have little responsibility to control themselves. White people learn that the locus of their control responsibility lies externally, and they learn to control others, often through violence, microaggression, gaslighting, manipulation, and other forms of overt or subtle abuse.

I believe this lesson can be reversed and dismantled. I believe it is the necessary work of white people to engage in, right now, for the sake of our collective survival.

I also believe in harm reduction. Because the danger of the unintegrated white self and society, the inability to take responsibility for one's own actions and the impact of those actions on others, is not a one-sided danger. Those of us who witness and understand this phenomenon, can make the conditions more or less dangerous for ourselves and others based on how much room we give to the behavior, how long we allow our boundaries to be violated, how much benefit of the doubt we give, and with how much resignation we move through the world.

Can we accept the danger for what it is, without collapsing in response to that danger?

And what then? If we are not to collapse, what are we then compelled to do about white danger? Because the danger of double-mindedness is not limited to the interpersonal, institutional, cultural, or even national realms. The danger of this phenomenon is playing out on a global scale, where the combination of bullish resistance to reality and reticent confusion at the consequences of bad behavior has masked the highly racialized difference between the U.S. public health response, and that of Black and brown majority nations. We are not doing well, and I believe it is not an exaggeration to say that our problem is psychological.

We must consider the role of a cultural orientation to violence and subjugation, inside the criminal mishandling of the COVID-19 pandemic response at the highest echelons of government and the most localized level of relationship. A narrative of white goodness, an unwillingness to respect the most basic social boundaries (social distance, wear a mask), and a warped relationship toward the humanity of others, plays no small role in the outrageously dangerous behavior of Americans, and may explain the sensibility that avoidable deaths are, in actuality, collateral we pledge towards economic prosperity. It is what sociologist Janine De Novais calls “worship” in the death cult of white supremacy.

What I know for certain: it is not up to white people to keep us safe, or to get us free. It never was. It never will be.

"What I know for certain: it is not up to white people to keep us safe, or to get us free. It never was. It never will be." - Autumn Brown, AORTA

Some years ago, I attended a retreat on race, love, and liberation, with Reverend angel Kyodo williams, a Black zen teacher and author. During the event, Reverend angel helped us to discern the difference between justice and liberation, noting that most conceptions of justice in an American context presuppose a condition where the group who has caused harm is in a position to give us justice. Liberation, she felt, was something altogether different.

In a context of global collapse, climate catastrophe, fascistic rise, and racial reckoning, I feel and see and experience daily the limitation of “justice” to give us protection, to heal us, to free us. So long as we engage the alternate reality circumscribed by the double-mindedness of whiteness, where boundaries are not boundaries and harm is not harm, we cannot be safe and we cannot be free. That way lies destruction. There is nothing more for us, or for them.

We must turn, and it must be now. If it is the work of white people to integrate themselves, so that they might heal, then it is the work of Black and brown people to free ourselves. So that we might live.

*This is different from the double-consciousness of black people, as described by W.E.B. DuBois in his 1897 autoethnographic work, The Souls of Black Folk, to describe the internal conflict experienced by Black people when having to view themselves through the racist gaze of white society.

The Revolutionary Power of Financial Education

We see a problem.

As professionals (and worker-owners) who work with a range of cooperatives, we see a pattern in who holds the finance positions in co-ops. This pattern is in line with social power, especially with regards to race and gender. Even in the multi-racial, multi-gender co-ops that we work with, the finance folks are often men and/or white folks, and frequently both.Maybe this is true for your co-op, too. Who holds the finance positions? Who has the most financial information? Who has confidence when talking about financial issues? Who tends to stay quiet, disengage, or go along with the group?

Why is this a problem? Well.

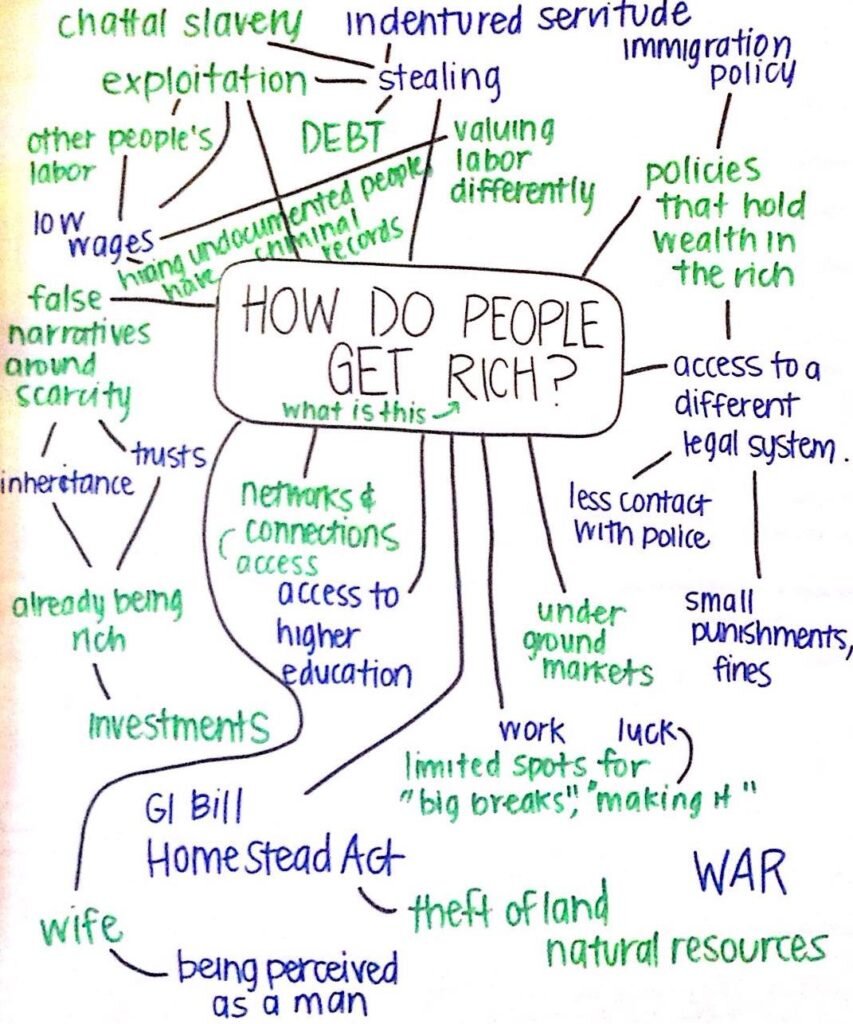

In short, this pattern is a symptom, a manifestation, and a result of racial capitalism, white supremacy, and patriarchy. It is a microcosm of larger systemic and societal inequity, violence, and theft of power.This pattern replicates and continues systemic power structures that cause a great deal of harm to communities of color, poor and working class communities, trans and gender non-binary communities, and women. It demonstrates the integration of systemic power structures into the decision-making processes of our co-ops.We are living in an extractive economy, an economy that functions to extract money, resources, and power from the majority of people, from the land, water, air and animals, and to then concentrate and enclose that power and resources into the hands of a very few. The extractive economy preys upon our people; it treats us as resources to be exploited. In doing so, it works intimately with the systems and practices of white supremacy, patriarchy, colonialism, etc. There are elaborate and large scale systems in place to remove the economic power from indigenous, black, and brown communities, from poor and working class communities, from trans and gender non-binary communities, and from women. It is not by accident that our communities that have been and still are being harmed by systemic power do not have high financial literacy skills. (We talk about this as a general trend. Of course individuals from these communities can and do have financial expertise. In fact, people who are poor and working class often build very developed budgeting and financial skills due to survival needs, and these skills often go unseen and undervalued in groups. We want to be very clear—do not allow larger societal trends to fuel stereotypes and assumptions about individuals.)Finance positions hold a lot of power. The people in finance positions help to shape much of the decision-making and dialogue of a co-op, deciding upon answers to questions like: What kind of information do we collect? What questions or decisions are important for us to be considering, with regards to our financial planning? Can we afford to give ourselves a raise? Do we need to raise our prices? Can we have retirement plans, or parental leave?These questions shape the framework of the group’s conversations. They are not strictly finance questions; they are values questions that the group as a whole should be empowered to figure out.

(We talk about this as a general trend. Of course individuals from these communities can and do have financial expertise. In fact, people who are poor and working class often build very developed budgeting and financial skills due to survival needs, and these skills often go unseen and undervalued in groups. We want to be very clear—do not allow larger societal trends to fuel stereotypes and assumptions about individuals.)Finance positions hold a lot of power. The people in finance positions help to shape much of the decision-making and dialogue of a co-op, deciding upon answers to questions like: What kind of information do we collect? What questions or decisions are important for us to be considering, with regards to our financial planning? Can we afford to give ourselves a raise? Do we need to raise our prices? Can we have retirement plans, or parental leave?These questions shape the framework of the group’s conversations. They are not strictly finance questions; they are values questions that the group as a whole should be empowered to figure out.

When a group defaults to one person or a small group of people to answer financial questions, the group as a whole becomes disempowered, and the answers to big-picture values questions are decided by a small minority.

“Co-ops are democratic, so everything that happens within them is democratic too,” is a common myth we encounter. However, the truth is that when members do not have the skills to participate in decision-making fully, or when a minority of members are holding a majority of the skills and power, this limits the democratic process. True democracy requires all members to have access to the information they need to participate. Without this, we have democracy in name only, with power structures insidious.We see a need, and a responsibility, to re-skill our communities, to redistribute power, to resist the operations of systemic power, and to revolutionize how we think about the responsibility of providing financial education and training within our cooperatives.

We also see an opportunity: we can intervene in systemic disempowerment.

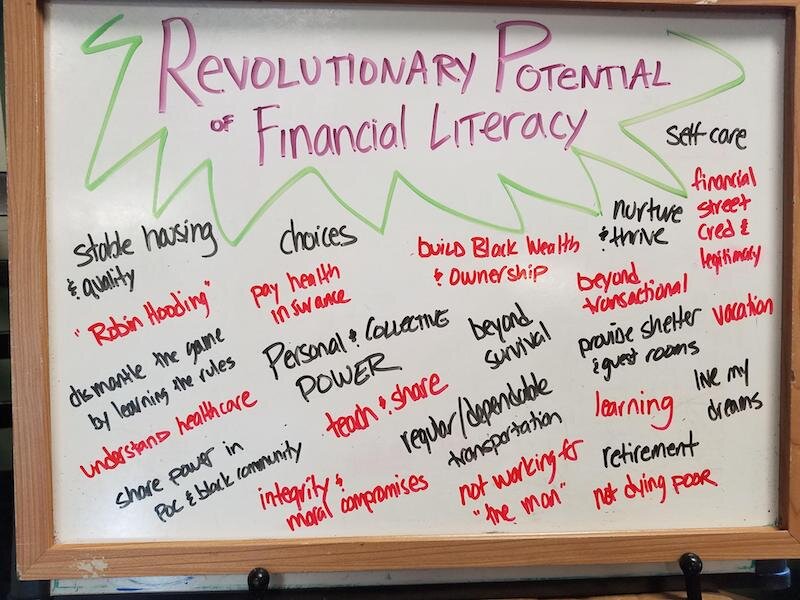

We have a lot to gain by taking a power analysis when addressing financial skills. We have a lot to gain by building the financial skills of every co-op member.It’s so common for people and organizations to request a list of things they can do to join in the work of countering white supremacy, patriarchy, classism, and other forms of systemic inequity. They want a list of answers—a tangible to-do list of clear-cut actions that can be checked off. This is understandable, to desire the work of transforming systemic violence to be clear, outlined, and concrete. And (unsurprisingly) most of the work is a bit more complex than that.However. This is tangible work.We can ensure that all co-op members are supported in developing strong financial skills. We can ensure that ALL MEMBERS: all indigenous, black, and brown folks, all poor and working class folks, all trans and non-binary folks, all women, are provided the education, training, and support they need to engage fully in the financial management of the cooperative.

As we do this, we will redistribute power. And as we redistribute power, we will build stronger co-ops.

Strong financial skills and high financial literacy are key skills needed for participating in the democratic ownership and management of a cooperative enterprise. Investing time, energy, and resources into building these skills in all members will benefit the co-op as a whole.As the whole group’s financial skills are elevated, more members will be empowered to participate more deeply in the democratic process of governing the co-op. It may change what kinds of questions the co-op is asking, who is answering the values questions, and what decisions ultimately get made.

Strong financial skills and high financial literacy are key skills needed for participating in the democratic ownership and management of a cooperative enterprise. Investing time, energy, and resources into building these skills in all members will benefit the co-op as a whole.As the whole group’s financial skills are elevated, more members will be empowered to participate more deeply in the democratic process of governing the co-op. It may change what kinds of questions the co-op is asking, who is answering the values questions, and what decisions ultimately get made.

Out of the hustle, and into the vision.

Just imagine: What could your co-op do if ALL of your members had strong financial skills? What could the broader co-op movement do?We understand strong, stable co-ops governed by members with solid financial skills to be a tangible way co-ops can be contributing to systemic change at large: Co-op Principle 7 (concern for community) in action. We see co-ops as organizational tools that can share resources like wages, benefits, and skills to strengthen individuals, families, and the communities they are part of. Co-ops can be a place where people gain access to the skills they need to break away from structures of systemic disempowerment, structures where white supremacy enforces and maintains a monopoly of access to information, power, and resources.

Stronger individual cooperatives will lead to larger and stronger cooperative (eco)systems.

We envision more successful businesses and increased wealth and ownership among communities that have had their wealth stolen from them for centuries. We envision economic empowerment and economic stability, leading to an increased ability to provide for each others’ basic needs. We envision people empowered and able to make decisions that go beyond survival with regards to things like access to housing, healthcare, and retirement savings.On a broader perspective, co-ops can (and do) play a role in skilling-up members of justice movements with financial skills, as well as skills in democratic governance, facilitation, etc. With more of us with strong financial skills, we envision an increased ability to organize for human rights that are often talked about in a financial lens, and are pushed aside because they have been deemed “not financially viable” (the right to healthcare, housing, clean water).The Financial Education Kit we are building is a contribution towards this vision.

It is designed not for the small finance team of a group, but rather for the group as a whole.

We are informed in this approach by the work of Jessica Gordon Nembhard, who in her book Collective Courage noted the key role economic study groups played not only in the development of black cooperatives, but also in the civil rights movement at large.The intention of this kit is that groups will go through it together, study-group style, towards the goal of increasing the financial skills of ALL members of the groups that use it. We are working hard to make that experience enjoyable and accessible, through interactive activities, games, and multimedia components such as recorded conversations and videos. The kit will be offered for download free of charge, in both English and Spanish. You can stay up to date on our progress, and support our work here.Additional ResourcesFrom Banks and Tanks to Cooperation and CaringMovement Generation Justice and Ecology ProjectFor a deeper dive into the extractive economy, its values and practices, as well as a framework for a just economic transition.The Movement for Black Lives Policy PlatformThe economic justice sections speaks to the need the for “economic justice for all and a reconstruction of economy to ensure Black communities have collective ownership, not merely access.”The Tyranny of Structurelessness, Jo FreemanFirst published in the 1970s, this article continues to be relevant today. It speaks more to the development of implicit power hierarchies in groups.

En Español

Poder revolucionario de la educación financiera

Vemos un problema.

¿Por qué es problemática esta situación? Bueno.

Para resumirlo, este patrón es un síntoma, una manifestación, y un resultado del capitalismo racial, la supremacía blanca y el patriarcado. Es un microcosmo de una mayor desigualdad social y sistémica, violencia y robo del poder. Este patrón se repite y continúa estructuras sistémicas del poder que causan mucho daño a las comunidades de color, comunidades pobres y de clase obrera, comunidades trans y de género no binario, y a las mujeres. Muestra la integración de las estructuras sistémicas del poder dentro de los procesos de toma de decisiones en nuestras cooperativas.Vivimos en una economía extractiva, una economía que funciona para extraer dinero, recursos y poder de la mayoría de las personas, de la tierra, el agua, el aire y los animales; y para entonces concentrar y encerrar ese poder y esos recursos en manos de unos pocos. La economía extractiva abusa de nuestro pueblo; nos trata como recursos a ser explotados. De esta manera, trabaja de manera íntima con los sistemas y las prácticas de la supremacía blanca, el patriarcado, el colonialismo, etcétera. Existen sistemas elaborados y a gran escala para eliminar el poder económico de las comunidades indígenas, negras y de todas las minorías, las comunidades pobres y de clase obrera, las comunidades trans y género no binario, y las mujeres. No es por casualidad que nuestras comunidades que han sido y todavía están siendo perjudicados por el poder sistémico carecen de una destreza financiera de alto nivel. (Hablamos de esto como una tendencia general. Por supuesto que los individuos de estas comunidades pueden tener experiencia financiera. De hecho, las personas que son pobres y de clase obrera a menudo desarrollan habilidades financieras y presupuestos muy avanzadaos debido a la necesidad de sobrevivir, y estas habilidades a menudo pasan desapercibidas e infravaloradas en grupos. Queremos ser muy clarxs, no permitan que mayores tendencias sociales impulsen los estereotipos y las suposiciones acerca de otras personas.) Los puestos financieros tienen un gran poder. Las personas en puestos de finanzas ayudan a darle forma a una gran parte de la toma de decisiones y el dialogo en una cooperativa, así determinan las respuestas a preguntas tales como: ¿Qué tipo de información colectamos? ¿Cuáles preguntas o decisiones son importantes a considerar, con respecto a nuestrx planificación financiera? ¿Podemos permitirnos un aumento de sueldo? ¿Necesitamos aumentar nuestros precios? ¿Podemos tener planes de retiro o licencia parental? Estas preguntas forman el marco de las conversaciones del grupo. No son estrictamente preguntas de finanzas; son preguntas de valores que el grupo entero debería tener el poder de determinar.

Cuando un grupo por defecto le otorga responder a esas preguntas a una persona o a un grupo más pequeño, entonces el grupo entero pierde su poder, y las respuestas a las preguntas grandes sobre los valores las deciden una pequeña minoría.

"Las cooperativas son democráticas, por lo que todo que suceda dentro también es democrático", es un mito común con el que nos topamos. Sin embargo, la verdad es que cuando lxs miembrxs no tienen las habilidades para participar plenamente en la toma de decisiones, o cuando una minoría de lxs miembrxs tienen la mayoría de las habilidades y el poder, se limita el proceso democrático. La democracia real requiere que todos lxs miembrxs tengan acceso a la información que necesitan para participar. Sin esto, tenemos una democracia solo en nombre, con estructuras de poder insidiosas. Vemos una necesidad y una responsabilidad, a capacitar de nuevo a nuestras comunidades, redistribuir el poder, resistir las operaciones del poder sistémico, y revolucionar la forma en que entendeos la responsabilidad de proveer educación financiera y capacitación dentro de nuestras cooperativas.

También vemos una oportunidad: podemos intervenir en el debilitamiento sistémico.

Tenemos mucho que ganar al emprender un análisis de poder cuando hablamos de las destrezas financieras. Tenemos mucho que ganar con el desarrollo de las destrezas financieras de cada miembrx de la cooperativa. Es muy común que las personas y organizaciones soliciten una lista de cosas que pueden hacer para participar en el trabajo de lucha contra la supremacía blanca, el patriarcado, el clasismo, y otras formas de la desigualdad sistémica. Quieren una lista de respuestas: una lista de tareas tangible de acciones claras que pueden tildar. Esto es comprensible, desear que el trabajo de transformar la violencia sistémica sea claro, delineado, y concreto. Y (como es de esperar) la gran parte del trabajo es un poco más complejo. Sin embargo. Es un trabajo tangible. Podemos asegurar que todxs lxs miembrxs de la cooperativa sean apoyadxs a desarrollar fuertes destrezas financieras. Podemos asegurar que TODXS LXS MIEMBRXS: todas las personas indígenas, negras y de todas las minorías, pobres y de la clase obrera, todas las personas trans y no binaria, todas las mujeres reciban la educación, la formación y el apoyo que necesitan para participar plenamente en la gestión financiera de la cooperativa.

Al hacerlo de tal manera, vamos a redistribuir el poder. Y al redistribuir el poder, construiremos cooperativas más fuertes.

Fuertes destrezas financieras y una educación financiera de alto nivel son habilidades clave para participar en la propiedad y gestión democrática de una empresa cooperativa. Invertir tiempo, energía, y recursos en el desarrollo de estas habilidades de todxs lxs miembrxs beneficiará a la cooperativa entera. En medida que elevan las destrezas financieras del grupo entero, más miembrxs tendrán el poder de participar de manera más profunda en el proceso democrático de la administración de la cooperativa. Puede cambiar el tipo de pregunta que hace la cooperativa, quién responde las preguntas de los valores, y cuáles decisiones se toman a fin de cuenta.

Fuera del bullicio y hacia la visión.

Imagínense: ¿Que podría hacer su cooperativa si TODXS sus miembros tuviesen fuertes destrezas financieras? ¿Qué podría hacer el movimiento cooperativista?Entendemos que las cooperativas fuertes y estables, que son gobernadas por miembrxs con destrezas financieras sólidas, conforman una manera tangible de las cooperativas contribuir al cambio sistémico en general: Principio 7 de Cooperativas (preocupación por la comunidad) en acción. Vemos a las cooperativas como herramientas organizacionales que pueden compartir recursos como los salarios, los beneficios, y las habilidades para fortalecer a los individuos, las familias, y las comunidades a las que pertenecen. Las cooperativas pueden ser lugares donde las personas acceden a las destrezas que necesitan para romper con las estructuras sistémicas de debilitamiento, las estructuras donde la supremacía blanca refuerza y mantiene el monopolio de acceso a la información, el poder, y los recursos.Las cooperativas individuales más fuertes conducen hacia fuertes y más grandes (eco)sistemas cooperativistas. Tenemos una visión de más negocios exitosos, mayor riqueza y propiedad entre las comunidades que han sufrido el robo de sus riquezas durante siglos. Tenemos una visión de la independencia y estabilidad económica, la cual conduce hacia una elevada capacidad de ver por las necesidades básicas de lxs unxs a lxs otrxs. Tenemos una visión de personas con la fuerza y la capacidad de tomar decisiones que van más allá de la supervivencia con respecto a cosas tales como el acceso a la vivienda, el cuidado de salud, y los ahorros de retiro. Desde una perspectiva más amplia, las cooperativas pueden desempeñar un papel en la capacitación de miembrxs de movimientos para la justicia para desarrollar destrezas financieras, así como también destrezas en la gobernación democrática, la facilitación, etcétera. Con la posesión de destrezas financieras entre más de nosotrxs, tenemos la visión de una elevada capacidad de organizar para los derechos humanos que a menudo se discuten con un lente financiera, y que son marginados porque no son considerados “económicamente viables” (el derecho al cuidado de salud, la vivienda, el agua limpia). El Kit de Eduacion Financiera que elaboramos es una contribución hacia la visión.

Lo diseñamos no para el pequeño equipo financiero de un grupo pero más bien para el grupo entero.

Nuestra orientación la informa el trabajo de Jessica Gordon Nembhard, quien en su libro Collective Courage, señaló el papel clave que jugaron los grupos de estudio económico no solo en el desarrollo de cooperativas negras sino también en el movimiento para los derechos civiles, en general.La intención del kit es que los grupos lo hagan juntxs, en estilo de estudio grupal, hacia la meta de aumentar las destrezas financieras de TODXS lxs miembrxs de los grupos que lo utilicen. Trabajamos duro para asegurar que la experiencia sea divertida y accesible a través actividades interactivas, juegos, y componentes de múltiples medios como conversaciones grabadas y videos. Ofreceremos el kit de forma gratuita para su descarga, en inglés y español. Puede mantenerse informadx de nuestro progreso y apoyar nuestrx trabajo aquí.

Recursos adicionales

From Banks and Tanks to Cooperation and CaringMovement Generation Justice and Ecology ProjectPara una inmersión más profunda en la economía extractiva, sus valores y prácticas, así como también un marco para una transición económica justa. Una Visión Para Las Vidas Negras [En Español]Las secciones de justicia económica hablan sobre la necesidad de la "justicia económica para todxs y una reconstrucción de la economía para asegurar que las comunidades negras tengan la propiedad colectiva, no sólo el acceso."The Tyranny of Structurelessness, Jo FreemanPublicado por primera vez en la década de los años 70, este artículo sigue siendo relevante hoy en día. Toca más el tema del desarrollo de jerarquías implícitas de poder en grupos.